- Home

- Member Resources

- Articles

- Genetic Counselors: Your Partners in Laboratory Medicine

As laboratory medicine becomes increasingly more complex, it is critical to have a laboratory team with diverse skills and expertise. For example, in recent years we have seen the emergence of specialized roles for informatics and digital pathology. For laboratories performing genetic testing, genetic counselors (GCs) have long been integral members of the laboratory team. However, GCs have a unique training and skill set that could even benefit laboratories that do not perform genetic testing. So how could a GC be a valuable addition to your laboratory?

Compared to medicine and nursing, the genetic counseling profession is young, with the first master’s level training program founded in 1969.1 Although the training has evolved and adapted over time, GCs remain grounded in genetics expertise, counseling and communication skills, and education.2 However, GCs now have expanded their roles and practices from those initially established in prenatal care and pediatric genetics into a diverse array of medical specialties. Our understanding of the human genome has increased rapidly over the past two decades, and the availability of next-generation sequencing technologies has led to more comprehensive testing options in both germline and somatic genetics. This has, in part, driven the expansion of GC roles in clinical laboratories, where there is increasing need for professionals to serve as a bridge between the laboratories generating complex test results and the providers and patients receiving those results.3 Furthermore, increasing commoditization of laboratory testing has led to the need for differentiators and value-added services like expert consults in subspecialty areas to help attract and keep clients.

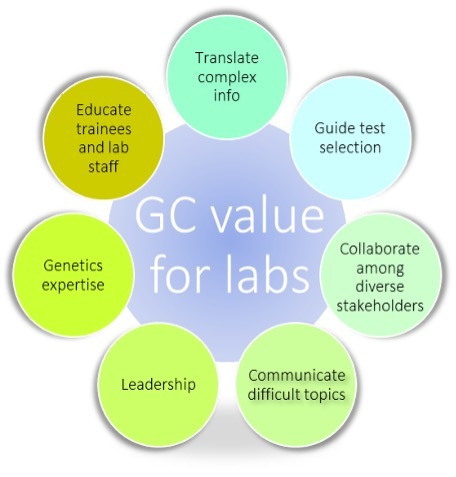

GCs have a well-established role in supporting genetic testing laboratories and their clients. Their genetics expertise is utilized in supporting pre-analytic activities, including order triage and support of billing and reimbursement teams for prior authorization, as well as post-analytic activities such as variant curation and report drafting, among many other activities. Beyond this obvious role, GCs have proven to be valuable team members in many aspects of clinical laboratory medicine outside of genetics laboratories (Figure 1).4,5 GCs train and practice in collaborative care settings, making them experts in interdisciplinary teamwork, connecting perspectives, and helping to find common ground among multiple stakeholders. Laboratory GCs serve on test development committees, laboratory quality/process improvement projects, marketing and business development initiatives, and many other cross-functional teams. GCs may even participate in projects outside the organization, such as liaising with laboratories and insurance providers to guide creation or updating of testing policies, a role supported by the PLUGS (Patient-centered Laboratory Utilization Guidance Services) network, a national laboratory stewardship collaborative. Even when not in formal managerial or executive positions, genetic counselors often find themselves “leading from the middle,” given their person-centered training focused on respect for autonomy and facilitating communication.6

GCs are also highly skilled in translating complex information. They assist laboratory colleagues in appreciating clinical decision-making and clinical providers in understanding the nuances of the laboratory results. This often includes being available by phone, email, and messaging applications for pre- and post-test consultations. GCs can discuss assay details and provide guidance to nurses and residents who often select tests and enter orders in the Electronic Medical Record (EMR), as well as discuss the clinical impact of test results. GCs are also adept at clearly conveying information in written form, which is key in providing accessible information about test options on laboratory websites and in the EMR, as well as crafting patient-friendly reporting language. For instance, GCs can work with laboratory services such as surgical pathology and hematopathology that rely on text-based, descriptive reports to develop templates to save time, promote consistency, and ensure reports can be easily understood by nonexperts while maintaining their medical accuracy.

Genetic counselors often are integrally involved in educational activities within clinical laboratories. They present continuing education content for medical technologists/laboratory scientists to expand their understanding of the medical conditions for which they perform testing. In one example, a GC presented a series of cases in which testing modalities across different clinical laboratory departments including hematopathology, biochemistry, molecular pathology, and cytogenetics contributed to comprehensive diagnoses for patients that would not have otherwise been possible. GCs also are integral faculty members in medical training, working to develop and present curricula for pathology residents and fellows.

GCs also play a key role in developing laboratory stewardship programs that improve patient care and contribute to effective use of health care resources.7,8,9 These roles include implementing systematic changes to the ordering process, working on projects for improved utilization of specific assays, or case-by-case review of complex or costly tests. One of our GC colleagues shared an example of investigating options for asparaginase activity, a test used to monitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients treated with chemotherapy. The GC confirmed CLIA accreditation, test cost, turnaround time, assay characteristics and reports, and reviewed all the information with the ordering oncologists to gain consensus to use a single lab.

Complex issues are routine in the clinical laboratory setting, including balancing needs of stakeholders, guiding test selection, reporting predictive/pre-symptomatic testing, handling incidental findings, and addressing duty to recontact.10 When true ethical challenges arise, they often require a disproportionate amount of time, energy, and skill to address. With their focus on collaboration and communication, as well as their training in principle-based ethics and ethics of care, GCs identify key concerns, facilitate discussion, and work toward resolution. In one case, a laboratory GC worked closely with the attending pathologist when an autopsy identified a likely genetic etiology for a patient’s death. Together, they discussed and navigated many issues related to pursuing genetic testing, providing justification for the cost, and informing the patient’s care team. They also ensured that family members were aware of the testing, agreed on its importance to understanding the cause of death, and were prepared for the potential implications for the health of other relatives.

As laboratory medicine continues to evolve, it is increasingly clear that GCs can serve in a diverse array of roles far beyond what the title of genetic counselor implies.11 With clinically oriented training that touches all aspects of medicine, along with strong education and collaboration skills, GC could also be shorthand for great communicators. With the ever-increasing complexity of pathology practice, we highly encourage the pathology community to explore the value that a GC can bring to your laboratory team.

References

- Marks JH, Richter ML. The genetic associate: a new health professional. Am J Public Health. 1976;66(4):388-390. doi:10.2105/ajph.66.4.388

- Cohen L. The de-coders: A historical perspective of the genetic counseling profession. Birth Defects Res. 2020;112(4):307-315. doi:10.1002/bdr2.1629

- Zetzsche LH, Kotzer KE, Wain KE. Looking back and moving forward: an historical perspective from laboratory genetic counselors. J Genet Couns. 2014;23(3):363-370. doi:10.1007/s10897-013-9670-7

- Cho MT, Guy C. Evolving roles of genetic counselors in the clinical laboratory. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2020;10(10):a036574.

- Waltman L, Runke C, Balcom J, et al. Further defining the role of the laboratory genetic counselor. J Genet Couns. 2016;25(4):786-798. doi:10.1007/s10897-015-9927-4

- Goodenberger ML, Thomas BC, Wain KE. The utilization of counseling skills by the laboratory genetic counselor. J Genet Couns. 2015;24(1):6-17. doi:10.1007/s10897-014-9749-9

- Kieke MC, Conta JH, Riley JD, Zetzsche LH. The current landscape of genetic test stewardship: A multi-center prospective study. J Genet Couns. 2021;30(4):1203-1210. doi:10.1002/jgc4.1403

- Conta, J.H. Laboratory Stewardship for Clinical Genetic Testing. Curr Genet Med Rep 7, 180–186 (2019). doi.org/10.1007/s40142-019-00175-6

- Kotzer KE, Riley JD, Conta JH, Anderson CM, Schahl KA, Goodenberger ML. Genetic testing utilization and the role of the laboratory genetic counselor. Clin Chim Acta. 2014;427:193-195. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2013.09.033

- Balcom JR, Kotzer KE, Waltman LA, Kemppainen JL, Thomas BC. The genetic counselor's role in managing ethical dilemmas arising in the laboratory setting. J Genet Couns. 2016;25(5):838-854. doi:10.1007/s10897-016-9957-6

- Means C, Wojcik A, Darnes D, Rolf B, McGruder C. Say my name, say my name: It's time to discuss the problem with the name "genetic counselor”, National Society of Genetic Counselors Annual Education Conference, Chicago, 2023, Oct 17-21.

Jacquelyn Riley, MS, CGC, LGC, is a laboratory-based genetic counselor in the Diagnostic Laboratories at Versiti in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, a national provider of specialty diagnostics for blood diseases. Prior to joining Versiti, Jacquelyn established the laboratory genetic counselor role at Cleveland Clinic, where she worked for more than a decade. In addition to being a lifelong learner in medical genetics, Jacquelyn is passionate about the power of collaboration, clear and effective communication, responsible use of healthcare resources, and continuous improvements to make our efforts extend as far as possible in helping patients.

Matthew W. Anderson, MD, PhD, FCAP, is a vice president and medical director of the Diagnostic Laboratories at Versiti, a national provider of specialty diagnostics for blood diseases. Dr. Anderson’s research interests include the use of next-generation sequencing technologies for clinical diagnostics and biomarker discovery.